Dakota translates to “friend” or “ally” and from time immemorial we have created alliances with many Indigenous and non-Indigenous Nations.

Our traditional government was called the Seven Council Fires or Oceti Sakowin—an alliance of seven Dakota, Lakota, and Nakota groups. Together, we formed a powerful kinship network that shared natural laws, spiritual beliefs, language, as well as vast trade and military ties.

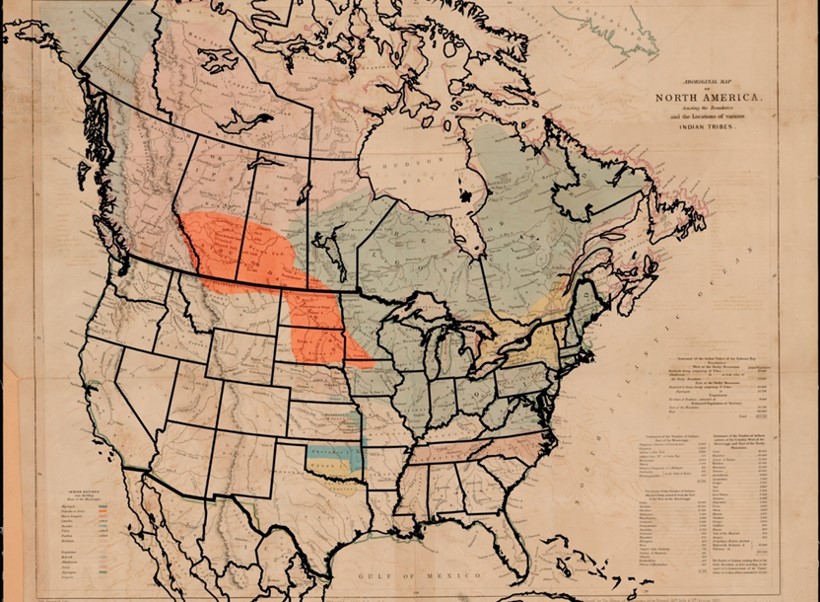

Today, members of the Oceti Sakowin are located across Canada and the United States.

The territories of the Dakota have long been misunderstood and misrepresented by non-Dakota people, who do not understand either the seasonal use of our territory or how our concept of kinship connects us to the land and our territory.

We were labelled Americans or nomads. This first label overlooks that our territories existed long before the establishment of the Canada-US border, while the second label overlooks that we had a well-defined and extensive territory that we shared with other Indigenous Nations.

As Dakota, our relations include the land and all things in our territory.

We are stewards of our lands and our environment.

Our traditional territory includes parts of what is currently southern Ontario, Manitoba, and Saskatchewan, extending into Wisconsin, Minnesota, North and South Dakota, and northern Montana.

Our Dakota ancestors followed the tatanka - buffalo, which supplied food, shelter, clothing, and tools. The river system also sustained us by providing food, medicines and water. The rivers, along with our ancient trails system, provided a vast travel network for trade and commerce with our Indigenous allies.

When European newcomers entered our territory we made alliances with them as well. We formed peace and trade agreements with the French in the mid 1600s and with the British Crown through ceremonies in the 1760s. The Dakota-Crown alliance was confirmed through the signing of a written treaty in 1787, which pledged peace, trade, and military alliance.

Our ancestors were crucial allies of the British in the American Revolution and the War of 1812. They helped defeat the Americans in several key battles.

Our Dakota warriors were commissioned officers in the British Army, and many more received medals in honour of their contributions in the fight against American expansionism.

For our support in the War of 1812, the British Crown presented King George Medals and promised to protect our rights and lands.

The British did not honour their promises; in the Treaty of Ghent in 1814, the British abandoned their Dakota allies and agreed to place much of Dakota lands under American control.

Although the Canada-US border was established at the 49th parallel in 1818, we continued to occupy parts of our northern territory, arriving on the prairies in the summer months to hunt, trade, and conduct ceremonies. Many treaties with our Indigenous allies were made or renewed at this time, including with the Nakota, Anishinaabe (Ojibwe), and Métis.

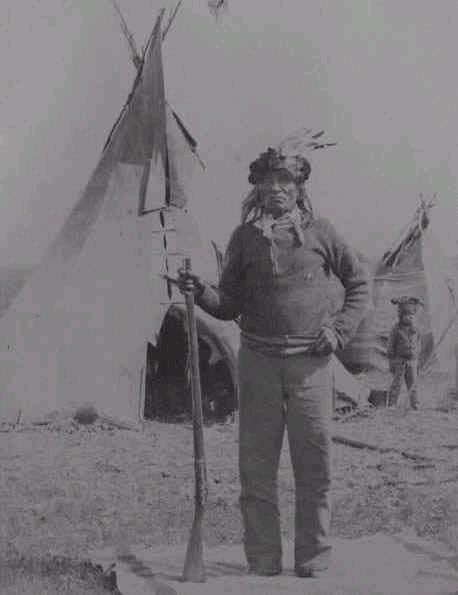

Some Dakota made treaties with the United States in an effort to live in harmony with settlers. In 1862, after enduring years of injustice, systematic treaty violations, and facing imminent starvation, an armed conflict with American settlers broke out. Hundreds of our Dakota ancestors moved to their northern territories led by Chiefs Tatanka Najin (Standing Buffalo), (Taoyateduta) Littlecrow and Wapaha Ska (Whitecap), seeking peace and fulfillment of the promises of their British allies.

The Chiefs brought with them the medals and flags given to them by the British in the War of 1812. They reminded colonial officials of their reciprocal promises, which the Crown refused to recognize.

Whitecap and his community continued their seasonal rounds through their territories on the prairies until forced onto reserve lands by the Canadian government in the 1870s.

Our ancestors settled in the current location in 1879, which was known as Moose Woods. This was an historic Indigenous hunting and trade area.

Chief Whitecap’s community strategically settled in this area known as Moose Woods, which had plentiful game, traditional plants, and access to the river. It was a traditional hunting and trading area spanning centuries, with an HBC outpost nearby. The community fostered social and economic ties with the nearby Métis communities like Round Prairie, and later with local settlers.

As a recognized founder of the City of Saskatoon, Chief Whitecap and his council advised settlers of the downriver location for the temperance colony in 1882.

At home, under the leadership of Chief Whitecap, they built a home for widows and orphans. They also lobbied for a school to be built in the community in the late 1880s

During the 1885 Resistance, Chief Whitecap and other Dakota men, including sons of Chief Whitecap, joined some of the local Métis who were on their way to Batoche. Some accounts say that the Chief was coerced into going to Batoche. Other accounts suggest that he was looking to advise and protect his family members at Batoche, as many Dakota families had kinship ties to Métis habitants at Batoche, including Chief Whitecap, whose daughter married a Métis man from that community.

At the battle at Fish Creek, Chief Whitecap was arrested, held captive at Humboldt with family. Charged with treason, he was then imprisoned in Regina where he awaited his trial. He was acquitted of all charges, partially due to the testimony of his Saskatoon friend, Gerald Willoughby, who attested that Whitecap was truthful, honest, and loyal to the Crown.

As the decades passed, the Whitecap Dakota continued to influence the area around them.

Our community developed a thriving cattle industry. From the 1890s until the late 1940s, a herd of nearly 300 head at its peak provided the community’s main source of wealth and food. Alongside of the cattle industry was hay production, which became another key source of income for the community. Families came together in the summer to cut hay in their shared haylands. Community members took hay to market in local towns and Saskatoon.

As Saskatoon grew, our Whitecap community took advantage of opportunities to share their culture with the city. In the first half century of Saskatoon, the Whitecap community accepted invitations to attend the opening of the Bessborough hotel in 1935, the Royal Visit in 1939, and participated annually in the Exhibition parades since the 1930s. Accepting the WDM’s invitation to showcase their culture at Pion-Era in 1955, is another example of Whitecap’s relationship to Saskatoon.

During World War II, seven of our members enlisted in the Canadian forces, with three men serving overseas. The community also made regular donations to the war effort. One of these veterans, Harold Littlecrow, was killed at the battle of Normandy after saving the life of a fellow soldier.

In 1959, Prime Minister Diefenbaker recognized the contribution of the Dakota to Canada’s history at the inauguration of the Diefenbaker Dam at Outlook, SK. In front of a crowd of thousands, Whitecap Dakota First Nation Chief Little Crow granted Prime Minister John Diefenbaker the honourary name Tatanka Mani (Walking Buffalo) as recognition of the Prime Minister’s efforts to aid First Nations people in Canada. This name that traces the history of the Dakota-Crown alliance, as the Dakota Chief Tatanka Mani was a signatory to the 1787 Treaty, and his son was a participant in the War of 1812.

The leadership of Whitecap, in consultation with their community, continually take major steps toward community revitalization, land stewardship, economic growth, infrastructure capacity, fiscal accountability, transparency, sustainability, and good governance.

Whitecap’s success is attributed to its commitment to the Dakota spirit of alliance. Much has been accomplished through partnerships with the business community, educational institutions, financial institutions, and other levels of government.

The results of this revitalization strategy include considerable economic benefits not only for the Whitecap community and its members, but for the entire region.

Contact Us